This book is the result of painstaking work done during the second half of 1979, mostly in Philadelphia, but also in St. Louis, Chicago, New York City and Washington D.C.

It includes a collection of materials from federal agencies such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the General Accounting Office (GAO); from community sources, such as Philadelphia and St. Louis Legal Aid Societies; and from independent sources, such as foundations, private corporations, books, private papers, etc.

The search for and collection of this material began in August, 1979, when housing activists in Philadelphia first stumbled across the strangely-worded theory called “spatial deconcentration.” A letter had been forwarded from the Philadelphia-area regional planning commission to activist attorneys in one of the legal service agencies announcing a new “fair housing” program called the “Regional Housing Mobility Program.” It might have been all greek to housing activists had they not already known that some type of sweeping master plan had already swung into effect to depopulate Philadelphia of its minority neighborhoods. The massive demolition operations in minority neighborhoods; which had been systematic, and the total lack of reconstruction funds from public or private sources spoke to that fact.

Activists had fought pitched battles with the city administration over housing policies for some three years before the word “mobility” was ever mentioned among their ranks. In march of 1979, in fact, Philadelphia public housing leaders launched an attack on a city organized and HUD sponsored plan to empty the city’s public housing high-rise projects. The question at the time had been: “Where will all the tenants go?” When the mobility program was unearthed in August, the answer fell into place like a major piece in a jig-saw puzzle. The answer, naturally, was the suburbs. It seemed to fit perfectly into the “triage” or “Gentrification” scheme, which froze the inner city land stocks for the returning suburbanites who were finding city life more economical than the suburbs.

Focussing their attention on this phenomenon called “Mobility,” the activists dug for more materials at the planning commission office. With the new materials available they began to slowly understand that the Mobility Program was much more than met the eye. By late September they only understood that the program seemed to be a keystone among federal housing programs and that HUD was making special efforts to avoid a confrontation over the matter.

It was tactically decided that the program was too massive to be fought on a local level. Activists in other cities would have to be sensitized to the Program and encouraged to swing into action against it. Between early November and late December, such contacts had been developed in St. Louis, Chicago and New York City — all key Mobility cities. All the information that had been collected in Philadelphia before November was distributed to community activists in these cities. This action helped uncover massive amounts of new information about the program, which would have been impossible to procure on the east coast for various reasons, and which changed the basic nature of the struggle the activists were waging against the government.

The Philadelphia housing leaders had fought their campaign between 1976 and 1979 under the assumption that their struggle against the land speculators and government bureaucracy had an economic base. They understood “gentrification” perfectly, but thought it had developed because the speculators were slowly but steadily viewing the land in minority neighborhoods as some kind of gold mine to be vigorously exploited at any cost. The information uncovered about the mobility program slowly taught them that they were entirely wrong, and perhaps this misdirection had prevented them from realizing any measurable amount of success in forcing the city or government to start-up housing construction projects in the city. It is now clear, in 1980, that instead of being economic the manifest crises that plague inner-city minorities are founded in a problem of control.

The so-called “gentrification” of the inner-cities, the lack of rehabilitation financing for inner-city families, the massive demolition projects which have transformed once-stable neighborhoods into vast wastelands, the diminishing inner-city services, such as recreation, health-care, education, jobs and job-training, sanitation, etc.; are all rooted in an apparent bone-chilling fear that inner-city minorities are uncontrollable.

Lengthy government-sponsored studies were conducted in the wake of the riots of the 1960s, particularly after the 1967 Detroit fiasco which cost 47 lives and was quelled only after deployment of 82nd Airborne paratroopers flown in from North Carolina which had been commissioned for duty on the emergency order of then-President Lyndon Johnson. Among intelligence agencies pressed into service to study the problem was the Rand Corporation. In late December, 1967 and early January, 1968, Rand was requested by the Ford Foundation to conduct a three-week “workshop” concerning the “analysis of the urban problem.” It was “intended to define and initiate a long-term research program on urban policy issues and to interest other organizations in undertaking related work. Participants included scientists, scholars, federal and New York City officials, and Rand staff members.

Johnson also ordered a particularly significant study of the riots to be commissioned which has led to the emergence of some of the most dangerous theories since the rise of Adolf Hitler. It was the National Advisory Commission Report on Civil Disorders, more commonly called the Kerner Commission Report. Strategists representing all specialities were contracted by the government to participate in the study. Begun in 1967 immediately in the wake of the Detroit riot, it was not published until March of 1968. But only weeks after its emergence, Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated and the most massive wave of riots that was ever recorded in American history almost forced a suspension of the Constitution.

Samuel Yette reported in his 1971 book, The Choice, that the House Un-American Affairs Committee, headed by right-wing elements, had put heavy pressure on Johnson to suspend the Constitution and declare martial law in the cities. Johnson resisted and instead ordered government strategists to employ the finest minds in the country to analyze the cause of the revolts and develop strategies to prevent them in the future.

The workshop participants were asked to prepare and submit papers recommending “program initiatives and experiments” in the areas of welfare/public assistance, jobs and manpower training, housing and urban planning, police services and public order, race relations, and others. The papers were grouped into four headings, including two called “urban poverty,” and “urban violence and public order.”

The Kerner Commission strategists came to the conclusion that America’s inner-city poverty was so entrenched that the ghettoes could not be transformed into viable neighborhoods to the satisfaction of residents or the government. The problem of riots, therefore, could be expected to emerge in the future, perhaps with more intensity and as a more serious threat to the Constitutional privileges which most Americans enjoy. They finally concluded that if the problem could not be eliminated because of the nature of the American system of “free enterprise,” than American technology could contain it. This could only be done through a theory of “spatial deconcentration” of racially-impacted neighborhoods. In other words, poverty had been allowed to become so concentrated in the inner-cities that hopelessness overwhelmed their residents and the government’s resolve to dilute it.

This hopelessness had the social effect of a fire near a powderkeg. But if the ghettoes were thinned out, the chances of a cataclysmic explosion that could destroy the American way of life could be equally diminished. Inner-city residents, then, would have to be dispersed throughout the metropolitan regions to guarantee the privileges of the middle-class. Where those inner-city minorities should be placed after their dispersal had been the subject of intense research by the government and the major financial interests of the U.S. since 1968. In the Kerner Commission Report, Chapter 17 addressed itself to this prospect. Suburbs were its answer: the furthest place from the inner-city.

A high proportion of the commissioners for the Report and their contracting strategists were military or paramilitary men. Otto Kerner, himself, chairman of the Commission, was the Governor of Illinois at the time of the Report but before that had been a major general in the army. John Lindsey, Mayor of New York City, had been chairman of the political committee of the NATO Parliamentarian’s Conference. Herbert Jenkins, before becoming a commissioner, had been chief of the Atlanta Police Department and President of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, a reputed “anti-terrorist” organization. Charles Thornton, the fourth of the seven commissioners, was chairman of the board of Litton Industries at the time he accepted his commission, one of the country’s chief military suppliers and, before that, had been general manager of the Hughes Aircraft Corporation — another major military supplier — and a colonel in the U.S. Air Force, a trustee of the National Security Industrial Association, and a member of the Advisory Council to the Defense Department.

The Commission’s list of contractors and witnesses was no less glittering in military and paramilitary personnel. No less than thirty police departments were represented on or before the Commission by their chiefs or deputy chiefs. Twelve generals representing various branches of the armed services appeared before the Commission or served as contractors. The Agency for International Development, the Rand Corporation, The Brookings Institute, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the International Association of Chiefs of Police, the Institute of Defense Analysis, and the Ford Foundation all played significant roles in shaping the Commission’s findings.

A hardly-noticeable name listed among the intelligence and military giants was that of one Anthony Downs, a civilian. Unlike most of the other contractors, whose names were followed by lines of titles, Downs was simply listed as being from Chicago, Illinois. His name was to become very prominent among inner-city grassroots leaders around the country by the end of 1979. Philadelphia housing leaders had remembered Downs as having been the author of the so-called “triage” report of 1975 which led to a storm of controversy at the time.

In his HUD-sponsored study, Downs argued that the inner-cities were hopelessly beyond repair and would be better off cleared of services and residents and landbanked. The middle-class should then be allowed to re-populate these areas, giving them a breath of new life. The activists, in their rush to uncover information about the Mobility Program, discovered, to their surprise, that Downs had written Chapters 16 & 17 of the Kerner Commission Report; the chapters devoted to demographic shifts in the inner-cities and spatial deconcentration.

Housing activists studying theories of “mobility” and “spatial deconcentration” stumbled upon yet another “strategist,” also, like Downs, out of Chicago, named Bernard Weissbourd. Weissbourd wrote two papers in Chicago in 1968 concerning the crisis of exploding minority inner-city populations. In one paper, entitled An Urban Strategy, he proposed a so-called “one-four-three-four” plan. Inner-city minority populations represented such a growing political threat by their growing numbers, he argued, that a strategy had to be quickly developed to thin out their numbers and prevent them from overwhelming the nation’s biggest cities. He proposed that this be accomplished through a series of federal and private programs that would financially-induce minorities to migrate to the suburbs until their absolute numbers inside the cities represented no more than one-fourth of the total population.

It is not clear if An Urban Strategy was written before the Kerner Commission Report was released or before the end of the Rand Corporations “workshop.” Around the same time, however, he wrote another paper entitled, Proposal for a New Housing Program: Satellite Communities. Weissbourd argued that the bombed-out inner-city neighborhoods should be completely rebuilt as “new towns in town” for the middle-class. As in his Urban Strategy paper, he discussed the threat of explosive inner-city minority populations and their threatening political power. He suggested that this threat could be repulsed with the construction of new housing outside the cities for inner-city minorities. He also suggested that jobs be found for these people in the suburbs and that “. . . some form of subsidy” be developed to induce them to leave the inner-cities. It is not clear whether Downs knew Weissbourd or borrowed his theories in time for his Kerner Commission Report, or if, in fact, the Report was finished after Weissbourd published his works, although it is likely, since both worked out of Chicago. It is clear that both strategists saw American middle-class life-styles as being challenged by the same explosive, racially-impacted inner-city neighborhoods.

In the same year that Downs had completed his Kerner Commission Report chapters and Weissbourd published his theories, President Johnson requested the formation of a research network that could focus on analyses of inner-city evolution and area-wide metropolitan strategies. This “thinktank” is called the Urban Institute. Since its founding in 1968, the likes of Carla Hills, Robert McNamara, Cyrus Vance, William Ruckelshaus, Kingman Brewster, Joseph Califano, Edward Levi, John D. Rockerfeller, Charles Schultze and William Scranton, have served as members of its board of trustees.

The five Blacks who have served, or are serving, are Whitney Young, Leon Sullivan, William Hastie, Vernon Jordan, and William Coleman; all prominent middle-class “yes-men.” The board of the Institute has had an interlocking relationship with the boards of trustees of the Rand Corporation and the Brookings Institute, both close CIA affiliates. Rand’s Washington office, in fact, is located in the same building where the Institute has its headquarters.

The Institute, to say the least, is a bizarre agency. It was supposedly founded in the spirit of harmony between the races, but has been dominated by a substantial number of presidential cabinet members and major U.S. corporations and Universities, such as Yale and Chicago. Worse, the Institute has conducted a substantial portion of the research that has led to the development of Mobility Program techniques. Its president, William Gorham, recently described the agency as a HUD “testing laboratory.” It is theoretically dominated by the likes of the quasi-military strategists that dominated the Kerner Commission, especially one John Goodman, the Institute’s major “mobility” specialist.

In terms of the types of experiments the Institute has conducted over its short history and the highly-sensitive nature of its research work, it ranks on a par with the CIA itself. Goodman, for instance, heading a team of strategists, developed, between 1975 and 1979, a series of experiments to determine the best way to induce inner-city Blacks and other minorities to leave the cities. A favorite ploy they developed was housing allowances and the so-called housing “subsidy” progress, whereby low-income families are supported in their rent payments, or paid cash grants, if they first agree to move out. Heavy experimentation was also conducted by the Institute on tactics that could be used to shape the Section 8 Program into a counterinsurgency tool against minorities.

In 1970, Downs wrote a little known book called Urban Problems & Prospects, in which he more graphically detailed the theory of spatial deconcentration. He developed a bizarre concept in the book entitled “the theory of middle-class dominance.” According to him, the dispersal of the inner-city populations to the suburbs could not be successfully completed unless and until a model of dispersal was developed whereby the artificially-induced outflow of minorities from the inner-cities would be controlled and directed to the point that they would not be permitted to naturally reconcentrate themselves in the suburbs.

This was the heart of the government theory which was later to become the theory of “integration maintenance.” This type of control had to be exercised, according to Downs, because white suburbanites would not remain stable in their bungalows if they were led to suspect that the incoming Blacks and other minorities were gaining power through their sheer numbers in the suburbs. The consistent theme of Down’s Problems, Chapters 16 & 17 of the Kerner Commission Report, and Goodman’s works at the Institute, was that of control.

The line of thinking about control found reinforcement in another book Downs wrote in 1973, entitled Opening Up the Suburbs: An Urban Strategy for America. Down’s theories from the Kerner Commission Report crystalized, taking as their cue his arguments laid down in Urban Problems. The theory of white “dominance” was carefully discussed in Suburbs. Included here were ideas for “. . . a broader strategy,” where “. . .a workable mechanism ensuring that whites will remain in the majority . . .” were produced. But Chapter 12 of Suburbs carefully laid down a mechanism which could transform the theories of his former works into practical application.

The chapter was called “Principles of a Strategy of Dispersing Economic Integration,” and laid down five basic concepts: 1 — establishing a “favorable” political climate for the strategy; 2 — creating “economic incentives” for the strategy; 3 — “preserving suburban middle-class dominance; 4 — rebuilding inner-cities; 5 — developing a further “comprehensive strategy.” In outline format, he analyzed each one. He noted that experiments should be conducted before the strategy was effectuated and that “. . . more effective means of withdrawing economic support . . . ” should be developed for the inner-cities to clear the way for landbanking inner-city neighborhoods.

To the amazement of the inner-city housing leaders across the country, Down’s theory of “dispersed economic integration” was exactly reproduced in HUD’s Regional Housing Mobility Program Guidebook, issued six years after Suburbs, in 1979.

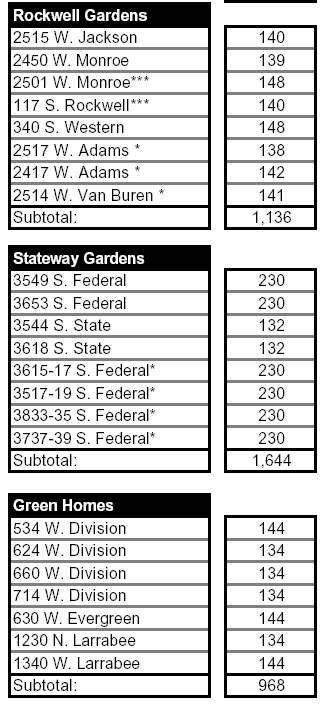

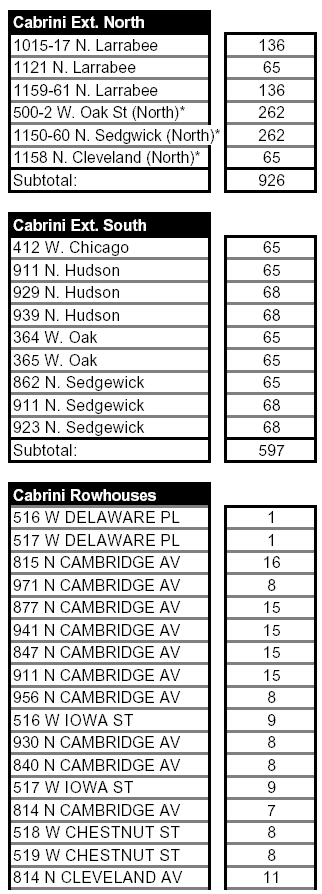

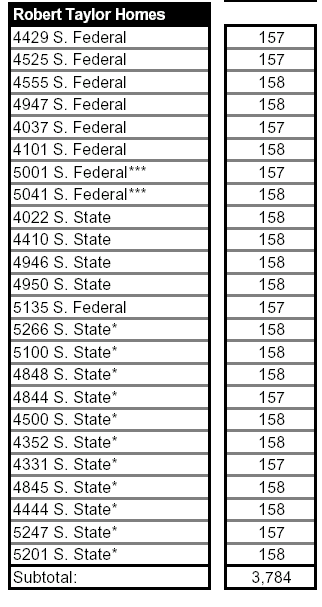

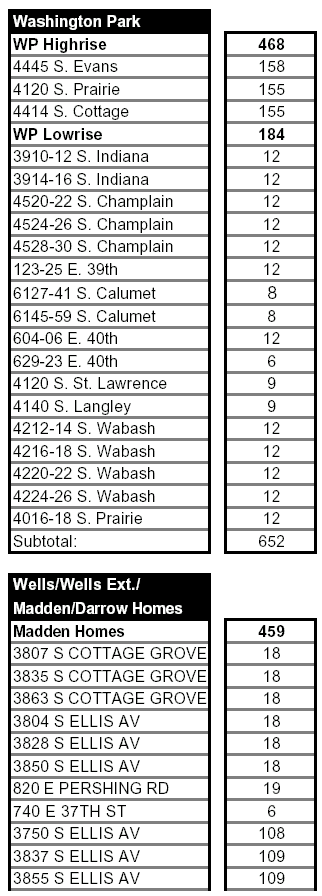

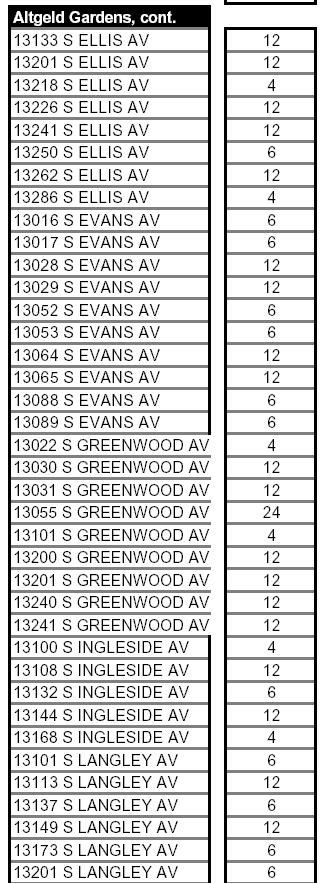

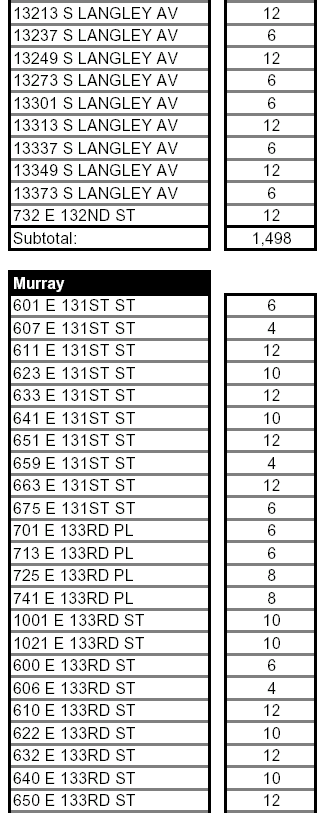

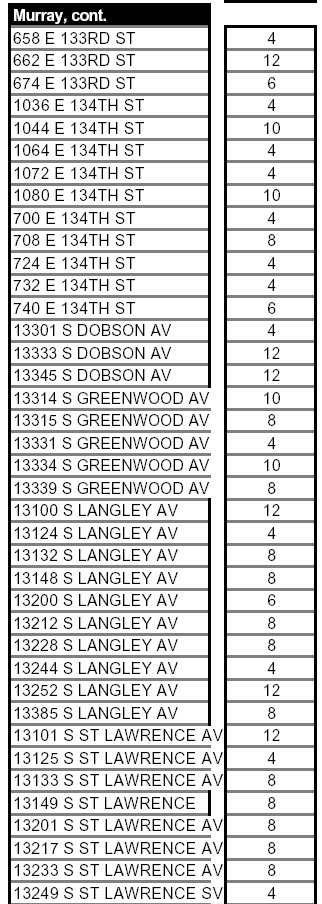

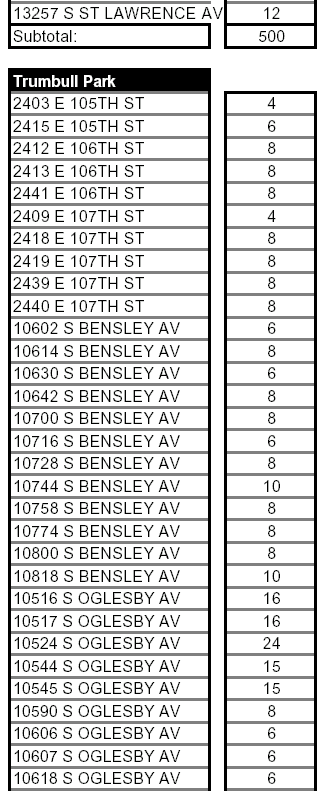

Also by 1977, a mysterious “fair housing” group in Chicago, the Leadership Council for Open Metropolitan Communities, was contracted by HUD to begin mobility programming experiments on Black high-rise public housing tenants in the Southside and Westside. It was called “The Gautreaux Demonstration Program” and achieved in two years the removal to the far suburbs of 400 families. Materials from HUD’s 1979 review of the Gatreaux experiment are included in this anthology.

By 1974, the Congress had enacted the Community Development Act. The legislation fused together the Urban Renewal programs of the Johnson era and the Revenue Sharing programs of the Nixon Administration. The title to the Act laid-out its theory: 1 — reduce the geographic isolation of various economic groups; 2 — promote spatial deconcentration; 3 — revitalize inner-city neighborhoods for middle and upper-income groups.

It wasn’t until 1975 that point four of Down’s theory in Suburbs, rebuilding the inner-cities, was fully analyzed. It was done in the form of the “triage” report, completed under HUD contract while he was still president of the Real Estate Research Corporation in Chicago; a firm founded by his father, James, some twenty years before. In this report, Downs made it clear that he wasn’t projecting the inner-cities being rebuilt for its present residents — the minorities — but for the white middle-class; the so-called urban gentry; a theory completely compatible with the Community Development Act of the previous year, Weissbourd’s 1968 writings, and the Kerner Commission findings. Under point four in Suburbs, Downs wrote that “. . . new means of comprehensively ‘managing’ entire inner-city neighborhoods should be developed to provide more effective means of withdrawing economic support from housing units that ought to be demolished.”

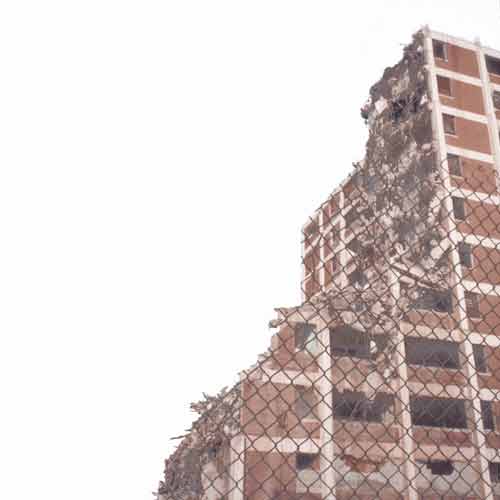

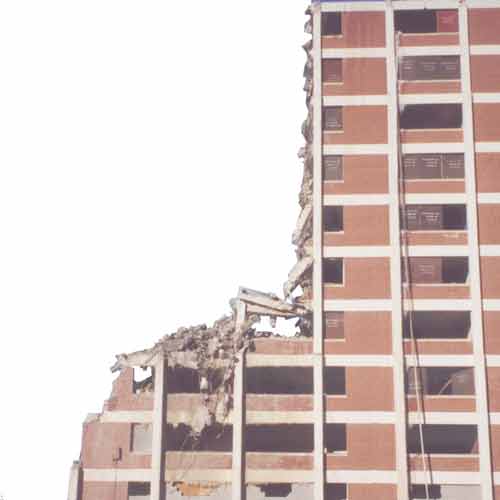

In his “triage” report, he wrote that Community Development funds should be withheld from inner-city neighborhoods so as to allow “. . . a long-run strategy of emptying out the most deteriorated areas. . .” A city’s basic strategy, he wrote, ” . . . would be to accelerate their abandonment . .. .” The land having been “banked,” it could be redeveloped for the gentry. He argued that instead of being given increased services, minority neighborhoods should be infused with major demolition projects.

When Patricia Harris became Secretary of HUD two years after the enactment of the Community Development Act and one year after the Section 8 Program replaced the Section 235 and 236 housing subsidy programs, the General Accounting Office, under the direction of Henry Eschwege, issued a stinging review of the Department’s policies. Noting that the Section 8 Program was the “. . . principal federal program for housing lower-income persons . . .” the 1978 report suggested, in threatening language, that “HUD needs to develop an implementation plan for deconcentration . . .” The report argued that “. . . freedom of choice . . .” was supposed to be the Department’s “primary intent,” but that top HUD officials were confused about the policy. HUD, the GAO insisted, was continuing to offer “revitalization” projects in the inner-cities, which was concentrating poverty in the cities. This policy, it stressed, was “incompatible” with spatial deconcentration.

In 1979, on the heels of the GAO report came HUD’s Regional Housing Mobility Program. The introduction of the program was itself bizarre, let alone the program. The emergence of the program was kept so quiet that virtually no grassroots community organizations in the country knew of its existence. The activists in Philadelphia had not even been aware of its existence until August of that year. It still wasn’t until November that grassroots leaders encountered an advisory council member to one of the planning agencies — and that was in St. Louis — who openly admitted that the program’s success depended on its “invisibility.”

On August 3, 1979, the planning commission directors of 22 pre-selected regions in the country were asked by HUD to gather in Washington to be schooled on the mechanics of the program. They were given Guidebooks and asked to return to their respective jurisdictions and prepare $75,000 to $150,000 applications for the program. The Guidebook made it clear that these regions had been specially selected because of their heavy concentration of inner-city minorities. They were instructed to contact major civil rights organizations and gain their “input” into the program. It was not coincidental that the National Urban League was one of the very few Black organizations that knew of the program’s existence. After all, Vernon Jordan, its president, sits on the board of trustees of the Urban Institute.

The Guidebook smacks of computer technology and is prepared with mind-control phrases, such as establishing “beachheads” in “alien” communities; initiating “. . . a long-term promotion of deconcentration;” identifying “. . . homeseeker traits which operate . . . on a process of suppression not selection;” and banking on the “. . . promotion of target areas” that “. . . will require that natural inclinations be altered.” True to the Down’s model established in Suburbs and Urban Problems, the Guidebook carefully analyzes the financial inducements to be used by the government to force minorities out of the cities and to force uncooperative suburban landlords to accept the program.

The Guidebook makes it clear that the program is intended for major expansion by 1982, when its funding base will be switched from HUD-Washington to an assortment of agencies, interestingly including the Community Development Block Grant funds, CETA, an the Ford, Rockerfeller and Alcoa Foundations. The CETA job component clearly traced its theoretical roots not only to Downs, but also to Weissbourd. The Guidebook also carefully lays out the use of the Section 8 Program as a primary base for mobility operations.

Once it became clear to inner-city housing leaders that the Mobility Program was nothing more than the first in a set of mechanisms the government intended to use to effectuate the ideas discussed in the Kerner Commission Report, it was easy to organize concerned people around the issue. It was actually a relief to some activists that proof had finally emerged of a real master plan, and not merely another fictionalized account of some remote possibility.

Less than one month after the Philadelphia leaders had made their final contacts in Chicago and New York City, a five-city conference was organized in Washington. Called the Grassroots Unity Conference, and held in January, 1980, it focussed on driving the message home to the government, through HUD, that the masterplan had been exposed and efforts were being organized in key regions of the country to stop it.

An almost violent meeting was held between top HUD officials and activists from Washington, Chicago, St. Louis, New York and Philadelphia during the two-day conference. A busload of inner-city residents literally invaded the Urban Institute offices and persuaded its staff to hand over dozens of documents that further reinforced community leader’s arguments that a masterplan existed, and that the Mobility Program was merely the first step in a new series of programs designed to systematically empty the inner-cities of their minority residents.

The friction slowly being generated between the government and the inner-city communities over this programming and its exposure has the potential of producing a major domestic crisis in the U.S. Housing and community activists have for years been confused about the nature of the deterioration of the inner-cities. The confusion often led to disillusionment and bitter dissension that sometimes created malevolent situations within the inner circles of community leaders and groups. Many community leaders knew that the government was not an innocent party to the problems of the cities, but few imagined the close association between it and private market forces in systematically driving the poor and the Black out of the cities.

Fewer still realized that the government had helped organize the “control” strategy from its inception. Now that the masterplan is being slowly uncovered by the persistent efforts of grassroots leaders and the confusion within community groups is evaporating, it may not be possible to vent their anger in non-destructive ways when the tale is finally told.

Some elements of the Black community, for instance, have argued for years that the government had declared a “secret war” on Blacks in America. Now evidence exists which makes the point difficult, if not impossible, to defeat. At least, an innocent observer must ask the question: “What kind of a government would allow these types of strategies to develop and thrive?” Even more to the point, one must ask: “How stable can a government be with such information emerging?” It now seems evident that the Constitution, which the Kerner Commissioners and the Johnson Administration feared was in need of special protections, does not apply to all people in America, but only the white middle class. The only way the government can now disprove this argument is to abolish all types of mobility programming and the “thinktanks” that shaped it.

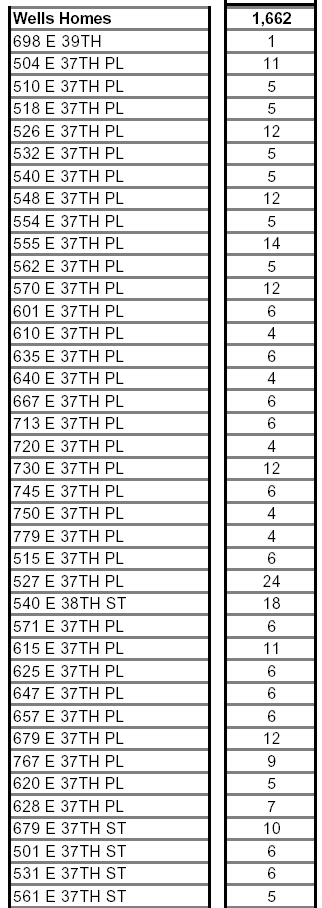

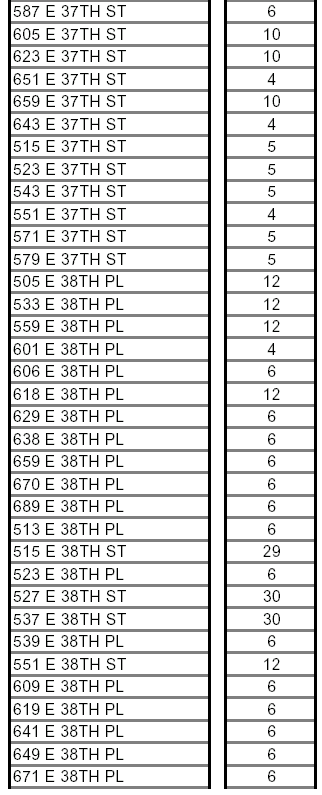

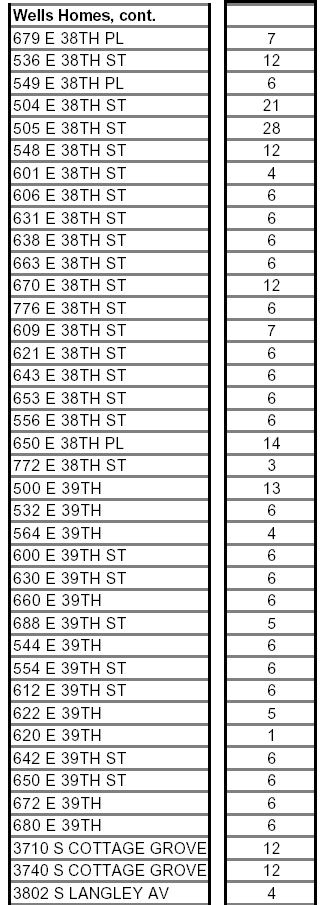

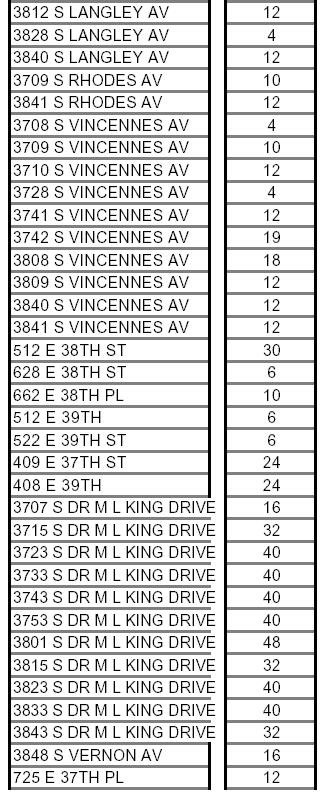

Researchers in all parts of the country who believe the government is traveling a lethal path are now uncovering major pieces of evidence to show the elaborate workings of the masterplan. Some of their arguments are enclosed in Part III of this book, under the title, “The Minority Response.” Other technical data are enclosed in Part IV and V. Of particular interest in Part V are the listings offered by the Urban Institute under housing allowance programs. Section 8 experimentation takes up a good portion of the available listings. A cursory examination of some of these papers — and in some instances a mere reading of the project titles — plainly shows the determination of the government to manipulate the Section 8 Program as a key instrument to force inner-city residents to move into the suburbs through the Mobility Program.

It aptly explains why these same researchers created the Section 8 Programs in the first place. Included in Part IV are lists of Boards of Trustees of the Brookings and Urban Institutes in Washington D.C. Attempts were made, in preparation for this edition to include a listing of the Rockerfeller and Ford Foundation’s Boards of Trustees. These corporations, however, refused to release their Annual Reports.

The exposure of the Mobility Program’s real intentions will hopefully change the direction of the government. If not, then the worse can be assumed for the future of the U.S. because no righteous people on the face of the earth would or should permit the existence of such policy, even if its dismemberment means inevitable confrontation or conflagration.

Several aspects of this mobility programming have deliberately been avoided at this time. Cyrus Vance, for instance, was Deputy Secretary of Defense at the time of the Detroit riot of 1967 and the initiation of the Kerner Commission Report. By 1980, Vance was Secretary of State, directly responsible for at least one organization named in the Report, the Agency for International Development (AID), widely reputed for its CIA ties. He was also a trustee of the Urban Institute along with Robert NcNamara, chairman of the World Bank and former Secretary of Defense under Johnson.

A reasonable question emerges at this point: Why is the military so closely attached to this mobility programming? Or, worse: What does the military intend to do in the event that this mobility-type programming fails, and the Blacks and other minorities remain in large part in the cities into the turn of the century, and riots create greater so-called threats to Constitutional safeguards? After all, Downs, himself, stated in Suburbs that he believed the mobility programming would fail. Is a repeat of the recent history of Greece or Chile the logical answer to these questions? Did the military, in 1967, issue an ultimatum to the government to remove the Blacks and other inner-city minorities to Black suburban “townships” in kid-glove fashion, with the option, in case of failure, being the iron fist? Furthermore, how could it have been possible for the surgical demolition operations in the minority neighborhoods of the cities to be so identical in all major American cities? Could any organization other than the Pentagon have done this?

These questions have been left unexplored because the weight of available documentation and the speed with which it is being collected and digested has been burdensome on anti-mobility forces. Further, this discussion about the military must be carefully explored by itself because of its obvious sensitivity. Also left for “Book II” is the discussion concerning the companion programs of the Mobility Program. Their successful exploration and revelation may make Watergate look pale by comparison.